O Fortuna, velut luna, statu variabilis,

O Fortune, like the moon you are changeable,

semper crescis, aut decrescis;

ever waxing and waning;

vita detestabilis nunc obdurat et tunc curat ludo mentis aciem,

hateful life first oppresses and then soothes as fancy takes it;

egestatem, potestatem, dissolvit ut glaciem.

poverty and power, it melts them like ice. – From Carmina BuranaA friend and I recently hiked to the top of Mount Lukens, the highest point in the City of Los Angeles at 5,000 thousand feet above sea level. I can see the top of Mount Lukens from my office window where it presents an unassuming aspect, just a long ridge rising slightly above the surrounding hills. I don’t give the mountain much thought except on winter days when I strain to see if the snow level has reached down to the top of the mountain. It rarely does.

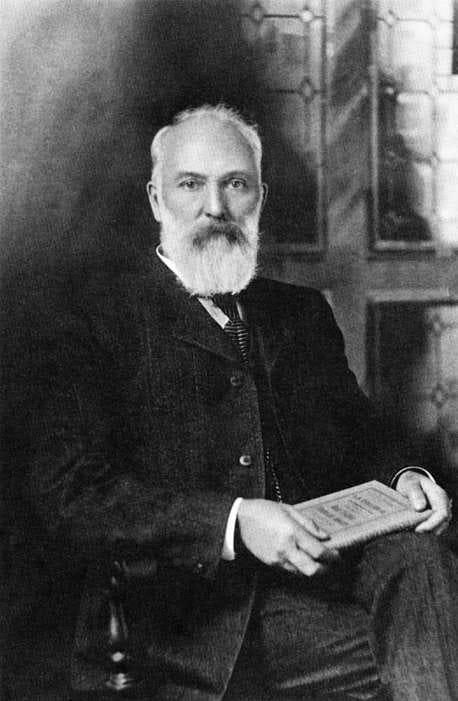

The mountain is named for Theodore Parker Lukens, and I had given him no thought at all before our hike. But when you spend over five hours walking up and down a mountain named for someone, you start to wonder: Who was this guy? Why was a mountain named for him? Lukens was a local figure, all but forgotten now, but he lived a life full of choices, of fortune and misfortune, with moments of beauty and moments of ugliness. And as forgotten as he may be, Lukens left a valuable legacy, if not the one he imagined.

Ascents

Our hike began on a cool morning in early April; I wore an extra layer and my friend wore gloves. We expected to warm up as we climbed, but every time I thought of removing a layer, the wind came up and chilled me anew. The air was clear, and we soon could see the top of the mountain looming above us. The climb was steady and occasionally steep as we hiked a well-worn trail on our way to the top. We chatted amiably as we made our way. When the grade steepened and the path narrowed, we interrupted our conversation as we worked to catch our breath and follow the trail.

The steepest part of our hike ended about two and a half miles in, after which we climbed gradually for another mile to a ridge, where the trail opened out to a gravel road used for maintenance of the antennas that bristle atop the mountain. We followed this road, the grade barely noticeable, for another mile until we reached the antenna farm. Along the ridge we noticed more rock outcroppings and less vegetation. The open landscape gave us a view into a distant valley, one I had visited but never seen from above. The new perspective revealed intrusive quarry cuts scarring the valley, which were not visible on my trips along the valley floor.

Theodore Lukens was born in Ohio in 1848 and at the age of six moved with his family to Illinois where his father established a nursery business. Just after his 20th birthday, Lukens signed up to serve in the U.S. Cavalry for five years; just eight months later he was honorably discharged for reasons that are now unknown. In 1871, at the age of 22, Lukens married Charlotte Dyer, who was 38 at the time, and opened his own nursery one town over from his father’s. Their only child Helen was born the next year. In addition to his nursery business, Lukens was active in civic affairs in the small Illinois town where he lived, serving as town tax collector, town trustee (similar to a modern city council member), and treasurer of a local fire company.

But Lukens suffered early setbacks. By 1877, he had endured a serious case of pneumonia, his business had been doing poorly, and he was deeply in debt. He confronted these challenges by choosing to leave Illinois for California, better weather, and better economic prospects. Despite his difficult business situation in Illinois, Lukens saved diligently for several years to finance the move. In October 1880, he boarded a train to Pasadena with $40 in his pocket, leaving behind enough cash for his wife and daughter to follow, which they did two months later. He also left behind $1,500 in unpaid bills.

Lukens arrived in Pasadena with no job and no place to live. On his first night off the train, he roomed at the Lake Vineyard House Hotel, working at the hotel to pay off his bill. Impressed with Lukens work, the hotel manager hired Lukens as zanjero, tending irrigation ditches for the Lake Vineyard water system. By the time Charlotte and Helen arrived, Lukens had earned just enough to set up his family in a two-room shack. Lukens had escaped Illinois’s harsh winters, but his economic situation was still dire. That soon changed.

Lukens arrived in Pasadena at just the right time. Seven years before he arrived, the area was mostly empty ranch land. Late in 1873, a group of Midwesterners purchased a large tract of the ranch, subdivided it, and started growing crops, mostly fruit trees and grapevines. When Lukens arrived in 1880, Pasadena was a growing farming community of about 400, with small businesses developing to support the residents. Lukens knew how to save on a meager income, and within a few years he had saved enough to pay off his creditors in Illinois, leave his job as zanjero, start a nursery business in Pasadena, move into a somewhat larger home, and begin buying real estate. Then, Pasadena boomed as Midwesterners arrived to vacation in the mild California winters and many decided to stay year-round. Lukens sold most of his real estate interests at the height of the market in 1886, allowing him to, as he said, “retire from active business” at the age of 38.

In just six years, Lukens had risen from menial labor to economic independence. He was now a respected citizen of the new town (Pasadena was formally incorporated in 1886): he had already served a term as justice of the peace, was active in the local Republican party, was a charter member of the Pasadena Board of Trade, and was active in establishing two libraries. Following his “retirement,” he remained active in business and civic affairs. In the 1890s he was President of the National Bank of Pasadena, served for six years on the city council, was twice elected by the council to serve as its president, and was a member of the Board of Trustees of the Pasadena Star newspaper and Throop Polytechnic Institute (now the California Institute of Technology).

Given his role in the fledgling community, it is no surprise that Lukens was embroiled in controversial issues. In 1885, he was one of 100 landowners who pledged not to lease property to any persons of Chinese heritage; there is no record of his role, if any, in an ordinance requiring all such persons to leave the city center within 24 hours, and the subsequent forced removal of up to 100 residents. Lukens wrote the first anti-saloon ordinance for Pasadena in 1886 (a major reason for the city’s incorporation) and continued to promote temperance in the community the rest of his life, dying just six months before Prohibition was adopted nationwide. In 1895, Lukens was serving his second term as president of the city council when the Southern Pacific Railroad sought to establish a rail line through town. Lukens alone opposed a city council resolution approving the line because the city was already served by the Santa Fe Railroad and he thought one railroad was enough; his colleagues promptly removed him from his position as president.

At the Top

We continued along the ridge until we reached the antenna farm, where an expansive view across the Los Angeles Basin opened up. The view in the other direction was less spectacular, dominated by half a dozen industrial antennas and boxy power sheds. A generator roared on just as we arrived and kept up a distracting grumble during our visit to the summit. The wind here was cold, and we huddled against a sunlit rock as we ate trail mix before beginning our descent.

As we walked through the relatively bare landscape near the mountain top, I wondered why there were no pine trees at this elevation. A year earlier, we had visited Henninger Flats, an area a few miles to the east of Mount Lukens. There, a little below the elevation at the top of Mount Lukens, we had rested in the shade of a small pine forest. But until we reached the very top of the ridge at Mount Lukens, we saw no pines. Then for a very short distance, just along the top of the ridge, we walked past a short line of pine trees. We appreciated the sighing of the wind in the pines, but they soon petered out and we were back in chaparral scrubland. At the time, I had no idea of the role Theodore Lukens played in bringing those pine trees to both Henninger Flats and the mountain named for him.

Lukens planned to spend his retirement “educating my daughter by traveling abroad” while maintaining his home in Pasadena. But most of his travels were local, and they inspired him in what became his life’s work: promoting the establishment of pine forests in the mountains just outside Pasadena.

Lukens started his career as a nurseryman in Illinois and he never really left it behind. As soon as his duties as zanjero permitted, he began growing trees in Pasadena. Instead of the hardwood trees he was used to in the Midwest, he experimented with pepper, live oaks, citrus, and eucalyptus, an Australian import. After achieving financial independence, and even more so after he was ousted as president of the city council, Lukens began to spend time hiking in the nearby San Gabriel Mountains and traveling to the Sierra Nevada Mountains of Northern California. Lukens joined the Sierra Club in 1894 and, after meeting John Muir on a trip to Hetch Hetchy Valley in 1895, he was active as a publicist for the then young organization. In the high Sierra Nevada Mountains he found abundant pine trees.

Lukens came to believe that establishing pines on the southern slopes of the San Gabriel Mountains above Pasadena would protect them from summer fires and winter debris flows. Lukens understood that pines—particularly his favorite, the Knob-cone Pine—were resistant to fire and could be planted densely to crowd out other species that were more flammable. The pines were also more likely to survive those fires that did start and to hold soil that otherwise washed down denuded slopes in winter rains. And, he thought, these pines would readily regenerate after fires, as their cones were opened by fire, spreading their seeds in the recently burned ground.

By the mid-1890s, Lukens had already experimented with growing pine in the San Gabriel Mountains. In 1892, he had planted pine seeds on property farmed by William K. Henninger, the area now known as Henninger Flats. Those efforts were not systematic, but through trial and error Lukens succeeded in establishing seedlings that survived into full grown trees. In January 1899, Lukens returned to the mountains above Pasadena and planted thousands of pine seeds at various spots in the San Gabriel Mountains.

Lukens initially pursued his forestation efforts largely on his own. He was a vice president and member of the board of the Forest and Water Association of Los Angeles County, but the forestation project seems to have been his own project. In February 1899, John Muir asked Gifford Pinchot, head of the Division of Forestry (later the Forest Service) in the U.S. Department of Agriculture, to appoint Lukens as Forest Supervisor for Southern California. No positions were immediately available, but a year later Pinchot appointed Lukens as a “collaborator” with the agency. Lukens was eventually named acting supervisor of the agency’s forests in the San Gabriel and San Bernardino Mountains.

The positions didn’t seem to matter to Lukens; far more important were the opportunities his association with the Forest Service gave him to continue trying to establish pine forests. The agency authorized Lukens to establish a tree nursery at Henninger Flats, and in 1903 the agency signed a lease there for a five-acre nursery. Lukens hired staff but quickly exhausted the allotted funds, leaving only himself and one other to build planting boxes, plant seeds, water and weed, replant seedlings, and prevent wildlife from undoing all their work. Still, he was able to propagate many seedlings, seedlings which made their way beyond the local mountains to Henry Huntington’s Pasadena gardens, to Los Angeles’s Griffith Park, to Forest Service headquarters in Washington, D.C., and to botanical gardens as far away as Chile and Australia.

The opportunities Lukens gained through his association with the Forest Service came at a cost. Lukens was used to working for himself but now had to contend with a government bureaucracy. Eventually, the bureaucracy wore him down. Lukens was forced to raise funds from the local community to continue his projects. In 1905, Pinchot vetoed a collaboration Lukens sought with the California State Forester. In early 1906, the Forest Service allocated Lukens money for 55 fire fighters, only to cut the allocation to 25 after Lukens had completed hiring. That summer, the agency refused to reimburse expenses Lukens had incurred on behalf of the agency. Lukens had had enough. On August 12, 1906, he resigned from the Forest Service in a terse telegram. The Forest Service repaid Lukens’s years of service to Southern California forests by demanding he return $66 it had allegedly overpaid him.

Descents

At the top of Mount Lukens, we had to make a choice: go back the way we came or take an alternate route down. We were naturally inclined to avoid retracing our steps in the name of variety, but a recent hiker had posted a review of the alternate route declaring it “boring”. That route also involved a questionable stream crossing; I had approached this stream from the other direction a few times and seen no way across. But the lure of variety won out. It was really no contest: the only thing more boring than a boring trail is seeing the same trail twice in rapid succession. And if our feet got wet at the stream crossing, we would be close to the end of the hike and could tolerate wet feet for a short while.

Halfway down the trail I concluded that the hiker who declared this route boring simply lacked imagination. He complained of a lack of views, but the views were simply more confined than sweeping and in fact took in the engaging complexity of nearby canyons. The chaparral here was varied, and in early spring many shrubs were budding and flowering. The grade was mostly gentle, and we appreciated the easy descent after the sometimes strenuous climb.

Nor was the stream crossing a problem. I hadn’t seen the way across from the other side because the trail ran along the stream bed for about 100 feet. We picked our way among rocks, but there was little water and we easily avoided getting our feet wet. The stream flowed through a small canyon, and the short climb out led us through a quiet, well-shaded glen with dense foliage. By now, the mid-day temperature and the lack of wind in the protected glen left us just warm enough to appreciate the shade. It was really the most pleasant part of the hike.

Lukens continued to dabble in forestation efforts after he left the Forest Service. He could, perhaps, have sought private support to continue his efforts to grow pine in the San Gabriel Mountains, but he went in another direction. In 1908, he acquired interests in and managed a project near San Luis Obispo that grew eucalyptus for use as timber and fuel. But within a few years the effort foundered as eucalyptus fell out of favor. Indeed, Lukens’s involvement in the project was cited as one of the reasons he was denied the position of California State Forester when he applied for the position in 1911 (the other reasons being his age—he was 63—and lack of formal training).

The U.S. Forest Service only operated the Henninger Flats nursery for two years after Lukens left, closing the facility in 1908. Lukens protested the closure, but he no longer had any influence at the agency. The Forest Service had determined that water was too expensive and access to the facility too limited. Seedlings still at Henninger Flats were moved to a facility at a higher elevation, adjacent to a stream, and closer to established roadways. It is reasonable to conclude that Lukens’s project was founded on a misconception: establishing pine forests in the dry chaparral environment at Henninger Flats and elsewhere in the lower elevations of the San Gabriel Mountains faced too many obstacles. Seedlings could be nurtured into self-sufficient trees with sufficient imported water and tending, but they could not survive the lack of water and browsing by local fauna without extensive human intervention. A few pine trees might be established in spotted locations, but a self-sustaining, expanding forest was always a long shot.

In his last years, Lukens largely focused on his family. His wife Charlotte had died in 1905, two years after suffering a debilitating stroke, and Lukens had devoted much of his time to her care. In 1906 Lukens married Sibyl Swett, a family friend, and adopted her Christian Scientist faith. In the following years, Lukens contended with the death of his son-in-law, his daughter’s ensuing financial difficulties, and his grand-daughter’s mental illness. He continued his association with John Muir and assisted Muir in the bitter, unsuccessful fight to prevent the damming of Hetch Hetchy valley in Yosemite National Park.

Lukens remained an active citizen of Pasadena and enjoyed a number of honors in his later years. He was made an honorary member of the Pasadena Board of Trade, recognizing his years of “conspicuous civic service.” The Los Angeles Times and the Pasadena Star each published complimentary features on his achievements. He was elected vice president of Pasadena Beautiful and, in something of an understatement, an honorary member of the Pasadena High School Forestry Club.

Lukens died in early 1918. Shortly after his death, friends established the Lukens Memorial Forestry Society. The Society promoted reforestation efforts for several decades, but has not been active since the middle of the last century. In 1969, Shirley Sargent published a short biography of Lukens; she titled her biography Theodore Parker Lukens: Father of Forestry.*

The Forest Service finally acknowledged Lukens’s efforts when it named Mount Lukens after him. The mountain had previously been named Mount Elsie, allegedly after a nun who cared for indigenous people in the area. But when her existence was called into doubt, a Forest Service official started adding Lukens name to the mountain on Forest Service maps. The designation became official in 1981, over sixty years after Lukens’s death.

Shortly before Lukens died, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors had met with him at Henninger Flats, praised the work he had done there, and promised to help continue the work. Finally, ten years after Lukens death, the County of Los Angeles established a forestry facility at Henninger Flats. The Los Angeles County Fire Department continued to operate a tree nursery at the facility for a number of decades, but it appears the nursery was not actively maintained after sometime early in this century. As recently as last year, an area around the nursery remained forested with pines nurtured by the nursery, though it is not clear to what extent they survived the Eaton Fire that swept through Altadena and the San Gabriel Mountains in January of this year.

The few pines I saw atop Mount Lukens were no doubt born from Lukens’ efforts at the nursery, as were others scattered here and there at lower elevations of the San Gabriel Mountains. Large stands of pine cover higher elevations of the San Gabriel Mountains, but those are native to the higher elevations and grew without human intervention. Seedlings from the Henninger Flats nursery may have made it around the world, but for all that Lukens was honored for his contribution to forestry, few of the trees he nurtured survive near Pasadena where he had hoped to establish dense pine forests.

Legacies

Out of the glen, another short descent led us back to our cars. It was early afternoon, and we had completed the ten-mile hike on a just few handfuls of trail mix, so we drove into town for lunch. We were pleasantly tired and enjoyed a sense of accomplishment. It is always rewarding to get to the top of something, to see the world from a new perspective, to have a story of a mountain climbed to pass on to others. But whether the mountain top is fulfilling or frustrating, it is not where we live our lives. We eventually return to the valley and its regular rhythms; to lunch.

In the years before he died, Lukens promoted the establishment of a park centered on a fifty-acre grove of Coast Live Oaks in Pasadena near the Arroyo Seco, not far from where Lukens drew water for the irrigation ditches he maintained when he arrived in Pasadena. Some of the oak trees have likely stood since the times of the Tongva people, who inhabited the area for thousands of years before Europeans arrived. In letters and public speeches, Lukens suggested that the natural grove of oaks “would be the nucleus for a fine, wild park,” going on to predict that “in a few years many hundreds of people annually will mingle with [the trees] and learn that they are a close connecting length between God and man.” Little came of the project during Lukens’s lifetime, and it was mentioned only in passing in Lukens’s biography.

A few years after Lukens’s death, Los Angeles County constructed Devil’s Gate Dam and reserved as parkland the area above the dam that Lukens had identified. The oak grove is now part of the Hahamongna Watershed Park, named for the Tongva village that once stood on the site. The park is managed by the City of Pasadena to, among other things, preserve native plants, habitat, water and other natural resources, just as Lukens envisioned.

About once a week, I walk several miles through this park, a short distance from my house. The park brightens my days as I stride among the oaks, watch egrets wading in the muck, find lupines blooming in spring, and wonder at the showy flowers of chaparral yucca towering above the shrubs in early summer. Another part of the park is home to picnic tables, sports fields, horseback riding facilities, and the world’s first permanent disc golf course, established in 1974. Not mere hundreds, as Lukens envisioned, but thousands of people visit the park every year. I suspect no more than a handful of those visitors know anything about Lukens and his efforts to promote the park.

Throughout his life Lukens, like all of us, enjoyed success and suffered failure. He participated in some activities that may make us cringe today, but chose to devote most of his energies to a noble vision of a mountain forested in pine. That vision was never realized. But a small project Lukens pursued as part of his regular civic engagement succeeded beyond his imagination. Lukens’ life and legacy remind us to continue through fortune and misfortune; our legacy may live on, acknowledged or unacknowledged, to enrich the lives of others in ways we little expect.

*I have relied heavily on Sargent’s biography in recounting Lukens’ life here. I would like to thank Leena Waller, Plant Science Librarian at the Los Angeles County Arboretum, for her assistance in locating a copy of this difficult-to-find book.